The debacle raised three broad questions: What will Biogen do next? Is the amyloid theory of Alzheimer’s now dead? And what else is going on in the Alzheimer’s drug development arena?

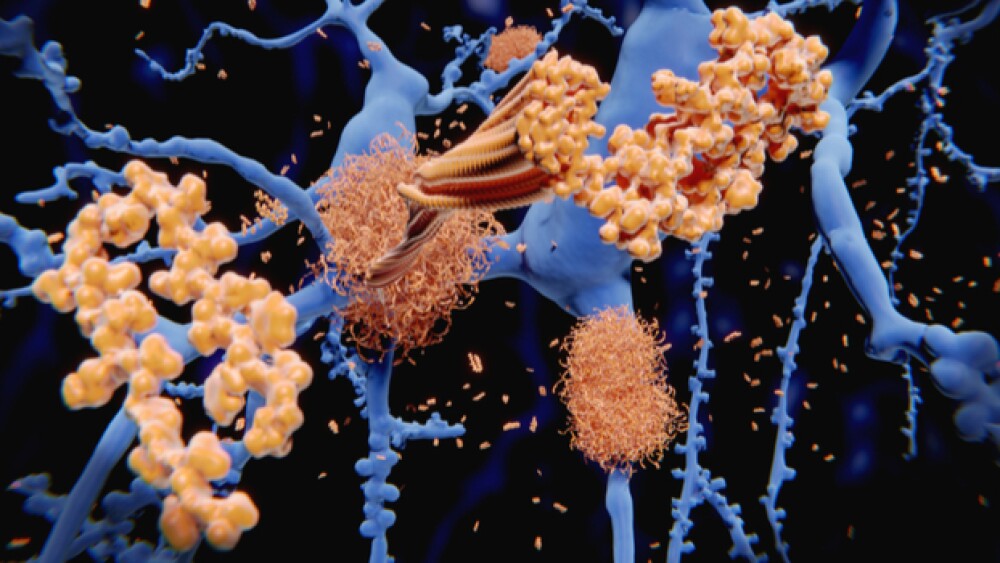

Illustration of the amyloid beta peptide, which accumulates to amyloid fibrils that build up dense amyloid plaques in Alzheimer’s disease.

Yesterday, Biogen and its collaboration partner, Tokyo-based Eisai, announced they were abandoning huge swaths of their Alzheimer’s program after the failure of aducanumab. The company lost over 26 percent of its share value, more than $15 billion in market value.

The debacle raised three broad questions: What will Biogen do next? Is the amyloid theory of Alzheimer’s now dead? And what else is going on in the Alzheimer’s drug development arena?

Biogen

Biogen has always been admirable for the way it swung for the fences, taking on big, challenging diseases. And when it made contact, it was huge for the company—a dominant portfolio in multiple sclerosis including Avonex, Fampyra, Plegridy, Tecfidera and Tysabri; Alprolix for hemophilia B and Electate for hemophilia A, Fumaderm for psoriasis (in Germany only), Gazyva for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (commercialized in the U.S. by Genentech), and the first-ever drug for spinal muscular atrophy, Spinraza.

But by putting so much of its resources and energy into Alzheimer’s and having it collapse, the company’s likely going to need to double down on its most promising drugs for nearer-term catalysts or buy something. Many analysts expect the company to cut back on its R&D budget. Forbes notes, “There might also be a push to drop programs deemed to be very risky or where the proof-of-concept requires long, expensive clinical trials. Finally, it wouldn’t be surprising to see Biogen become aggressive in their M&A activities. But make no mistake. The death of an important drug like aducanumab will have both a short and a long-term effect on Biogen as a company and especially on R&D.”

Is Amyloid Dead?

The amyloid theory is that the accumulation of a protein called amyloid-beta in the brain is the cause of dementia and cognitive damage. However, the Biogen trial and many, many other drugs that prevent or clear amyloid have failed to improve cognition in even early Alzheimer’s patients.

Rudy Tanzi, Chair of the Cure Alzheimer’s Fund Research Leadership Group and the Kennedy Professor of Neurology at Harvard University and at Massachusetts General Hospital, told BioSpace earlier this year, “I think amyloid and tangles trigger the disease, but they’re not sufficient to cause dementia. In a nutshell, what we’ve learned is that amyloid comes very early, 15 years before symptoms. And all the genetics tells us this disease begins with amyloid.”

He believes that when amyloid begins to form, the tangles themselves kill some neurons, but not enough to create dementia. But the amyloid and tangle-driven neuronal cell death eventually hits a point where the brain’s innate immune system reacts with significant levels of neuroinflammation, which is where the real cell death occurs, leading to dementia.

Tanzi compares the amyloid to a match and the tangles to a brush fire. “You can live with them,” he said, “but once the brain reacts to neuroinflammation, that’s like the forest fire. That’s when you really lose enough neurons to go downhill and become dementia. The failure of the amyloid-targeted AD trials is like trying to put out a raging forest fire by blowing out the match.”

Interestingly, James Kupiec, chief medical officer of ProMis, a biotech company working to develop antibody therapeutics for neurodegenerative diseases, notes, “Aducanumab was developed over a decade ago to go after plaque, which we have since learned is the incorrect therapeutic target because plaque is a largely non-toxic form of amyloid beta. Aducanumab wasted too much limited ammunition on the wrong target, which also led to the dose limiting side effect of brain swelling (edema). Unlike aducanumab, ProMIS’ lead antibody candidate for Alzheimer’s, PMN310, reflects key lessons learned, namely that the toxic oligomer of amyloid beta is a root cause of AD, not plaque. PMN310 is the first antibody to selectively target just the toxic oligomer, a misfolded, toxic form of amyloid beta, offering a potential significant advantage over aducanumab and other less selective antibodies in terms of both efficacy and safety.”

Whether ProMIS is on the right track remains to be seen, but few scientists in the field dismiss the amyloid entirely but believe that neuroinflammation is a big part of the story, and that it’s possible that clearing amyloid doesn’t undo the damage to the brain that has already been done. Several companies are working on ways to tamp down neuroinflammation, and increasing blood flow to the brain.

But again, not enough is really known about the disease or the brain yet. For example, most researchers believe that microglia, specific immune cells in the brain, are involved in the disease. But no one is completely sure whether they protect or hurt. There is evidence that they protect against Alzheimer’s, because when they’re damaged, the risk of the disease increases, but there is also evidence that when they’re overactive, they can damage neurons.

Pipeline

Meanwhile, a number of companies, such as the ProMIS mentioned above, are still working on developing drugs, using a variety of approaches.

Eisai and Biogen. Despite yesterday’s announcement, Eisai and Biogen aren’t completely done. Eisai announced today that its Phase III trial of BAN2401, an anti-amyloid beta protofibril antibody, has started. It will look at 1,566 patients with mild cognitive impairment from Alzheimer’s or mild Alzheimer’s disease dementia with confirmed amyloid pathology in the brain.

Roche. Although Roche’s crenezumab failed two Phase III trials and the company decided to discontinue CREAD 1 and 2 in January, the drug is still being studied in the Alzheimer’s Prevention Initiative (API) trial in a study population from that program—cognitively healthy people in Columbia with an autosomal dominant mutation who are at risk to develop familial Alzheimer’s disease.

ACADIA Pharmaceuticals. The company has an ongoing Phase III HARMONY trial evaluating the efficacy and safety of pimavanserin for the treatment of hallucinations and delusions associated with dementia-related psychosis.

AC Immune and Roche. On February 20, 2019, AC Immune indicated that Roche’s Genentech was recruiting patients for a second Phase II trial for an anti-Tau monoclonal antibody, MTAU9937A in moderate Alzheimer’s disease. It is also being studied by Genentech in a separate Phase II trial under the RG6100 identifier.

Denali Therapeutics. Denali has several drugs in the pipeline for Alzheimer’s, including DNL747, ATV:TREM2 and ATV:Tau. On February 15, 2019, the company announced it had dosed its first patient in a Phase Ib trial of DNL747 in Alzheimer’s disease in collaboration with its partner Sanofi.

Although the Biogen failure was a big hit, each failure generates a better understanding of the disease and brain function. These companies are only a few still working in the Alzheimer’s arena.