Phase II data showed the triple combination treatment provided 16 months of progression-free survival of patients.

A team of researchers from University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) may have found a combination treatment for a type of advanced melanoma. The researchers combined a checkpoint inhibitor and two target therapies to extend the lives of patients.

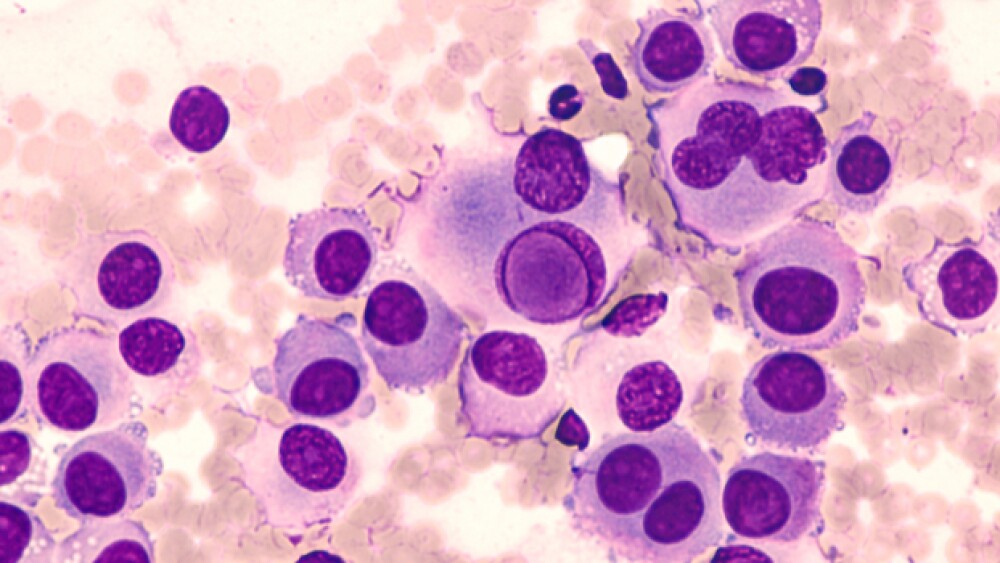

The researchers combined Merck’s Keytruda (pembrolizumab) with dabrafenib and trametinib, two BRAF inhibitors as a front-line treatment for the disease. UCLA reported that the combination treatment shows promise in progression-free survival for patients with a type of melanoma that contains a potent gene mutation, BRAF V600E. In addition to the efficacy, UCLA said the triple combination did not cause any debilitating side effects. The team of researchers published the results of a Phase I and Phase II trial in the journal Nature Medicine.

In the Phase I trial, the combination treatment was tested for safety in 15 people with BRAF-mutated metastatic melanoma. In 11 of them, the tumors shrank and remained stable and did not grow again for 12 to 27 months, UCLA reported. Data from the Phase II trial, which included 120 patients, showed that the patients treated with the three-drug therapy had progression free survival for an average of 16 months. The triple combination was pitted against a combination of dabrafenib and trametinib and a placebo. Patients on that arm had an average of 10.3 months of PFS. It was a 1:1 study.

About half of the 94,000 people diagnosed with melanoma each year in the United States carry the BRAF mutation. Around 7,000 people die each year from this cancer.

Antoni Ribas, the senior author of the UCLA research papers and director of the UCLA Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center’s Tumor Immunology Program, said the combination treatment “sensitized the patient’s own immune system to bolster the power of immunotherapy and block the growth of two genes — BRAF and MEK — that cause cancer cells to reproduce and grow out of control.”

UCLA noted that previous studies of this type of melanoma showed that one of the three drugs tested in these trials has had a positive impact on shrinking tumors.

However, most of the patients who received a single drug regimen relapsed. Two-drug combinations have also shown limited success, UCLA noted.

Earlier attempts to combine one of these medications with a checkpoint inhibitor like Keytruda were also not successful due to the toxic side effects that made them dangerous to use, Ribas told the UCLA newsroom. In February, Keytruda was approved for the adjuvant treatment of patients with melanoma with involvement of lymph nodes.

“We found that by using two targeted inhibitors, instead of just one, in combination with a checkpoint inhibitor, we could safely and effectively treat the cancer,” said Ribas, who is also the director of the Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy Center at UCLA. “With this triple combination, we’re doing two things at once: using the two inhibitors to block the cancer from spreading, and stimulating the immune system. An immune response has the ability to remember foreign invaders and help protect the body from similar infections in the future, so enlisting an immune response to the cancer is aimed at having more durable responses to the therapy.”

The UCLA study was by Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., as well as the Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy and the National Institutes of Health. UCLA did not report whether or not the data from this trial would be moved into a Phase III study.