The research team found that some pancreatic tumors create a molecule that helps enable the spread of the cancer cells.

A team of scientists believes they may have discovered a method to prevent the spread of pancreatic cancer and improve the outcome for chemotherapy patients.

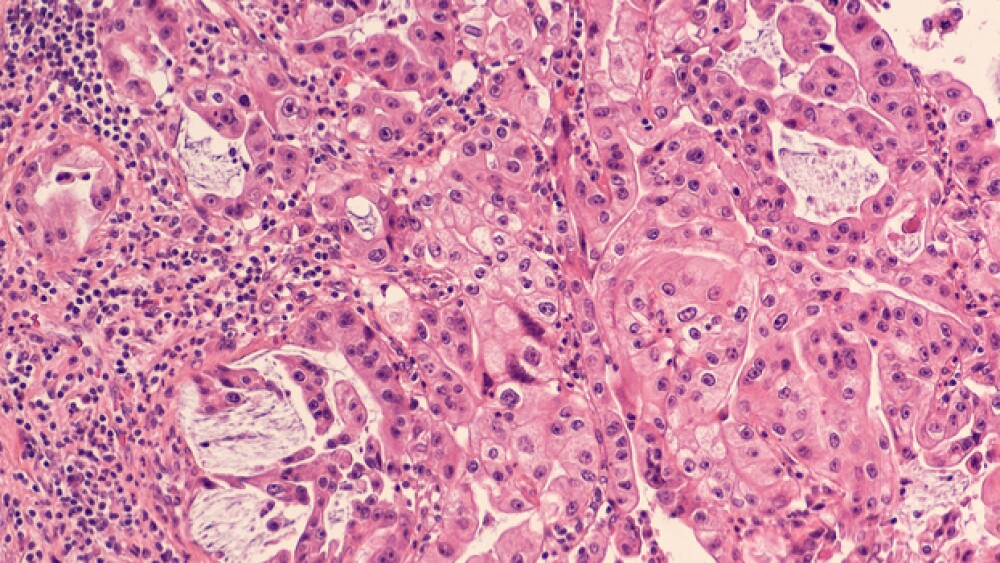

This morning, researchers affiliated with the Garvan Institute of Medical Research in Australia reported evidence that shows aggressive pancreatic cancer cells can actually change the surrounding environment to “enable easy passage to other parts of the body,” which is the main cause of pancreatic cancer-related death. In a statement issued this morning, the researches announced the discovery that some pancreatic tumors produce a molecule called “perlecan” that reshapes the environment surrounding the tumor, which then allows the cancer cells to spread more easily to other parts of the body. Additionally, that molecule also creates a protection against chemotherapy. In a mouse model, the researchers showed that lowering the levels of perlecan revealed a reduction in the spread of pancreatic cancer and improved response to chemotherapy. The findings were published in the journal Nature Communications.

Paul Timpson, head of the Invasion and Metastasis Laboratory at the institute, noted the aggressive nature of pancreatic cancer. He said by the time most cases are diagnosed, the tumor is often inoperable.

“What we’ve discovered in this study is a two-pronged approach for treating pancreatic cancer that we believe will improve the efficiency of chemotherapy and may help reduce tumor progression and spread,” Timpson said in a statement.

With the low-survival rate of pancreatic cancer in mind, less than 9% in Australia, the Garvan-led team wanted to understand why some pancreatic cancers spread, while others appear to stay in one place. Taking what they called an unconventional path, the researchers compared the tissue around tumor cells in patients with metastatic and non-metastatic pancreatic cancers. The tissue, which they called “the matrix” acts as a glue to hold different cells in the tumor together.

In mouse models, the Garvan team extracted fibroblasts, the cells that comprise the matrix, from both pancreatic tumor types. When the different fibroblasts were mixed with cancer cells, the researchers found that cancer cells from a non-spreading tumor began to spread when mixed with fibroblasts from a spreading tumor.

Claire Vennin, first author of the published research, said the results suggest that some pancreatic cancer cells can “educate” the fibroblasts in and around the tumor.

“This lets the fibroblasts remodel the matrix and interact with other, less aggressive cancer cells in a way that supports the cancer cells’ ability to spread,” Vennin said in a statement. “This means that in a growing tumor, even a small number of aggressive metastatic cells -- a few bad apples -- can help increase the spread of other, less aggressive cancer cells.”

In the study, the researchers found that by reducing the levels of perlecan in mouse models with aggressive metastatic pancreatic cancer through a gene-editing process, it reduced the spread of the cancer and increased the response to chemotherapy.

Timpson noted that most cancer therapies on the market are aimed at the cancer cells themselves. However, he said their research shows the environment around the tumors is a “potential untapped resource for cancer therapy.” The Garvan team intends to explore that further, he said.