A growing body of evidence has found that teen brains can be structurally changed by spending long spans of time playing games, watching videos and other activities on digital screens.

Study of kids ages 3 to 5 suggests that digital media use ("screen time") impacts development of brain areas responsible for visual processing, empathy, attention, complex memory and early reading skills

CINCINNATI, Nov. 10, 2022 /PRNewswire/ -- A growing body of evidence has found that teen brains can be structurally changed by spending long spans of time playing games, watching videos and other activities on digital screens (i.e., "screen time"). Now, a study led by experts at Cincinnati Children's reports that high amounts of screen time can affect brain growth and development at much earlier ages.

The study, published Nov. 9, 2022, in Scientific Reports, was led by John Hutton, MD, MS, and colleagues at the Reading and Literacy Discovery Center at Cincinnati Children's. It involved acquiring MRI scans in 52 healthy children aged 3 to 5 and analyzing brain structure according to each child's digital media use.

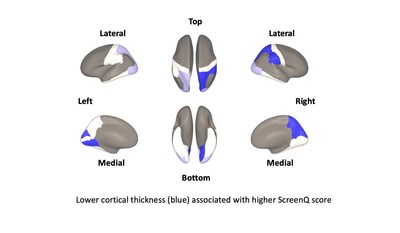

The MRI structural measures were cortical thickness (CT), which measures the thickness of the surface of the brain's "gray matter"; and sulcal depth (SD), which measures the depth of "canyons" between brain folds. Both are established measures of brain development linked to differences in a range of abilities.

To estimate media use, the team used ScreenQ, a composite measure developed at Cincinnati Children's reflecting American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) media use guidelines. The measure includes access to screens (e.g., in bedrooms, meals), frequency of use (e.g., hours/day), content and parent-child use together. The analyses were controlled for child age, sex and maternal education level.

The team found that higher media use was associated with lower CT and lower SD for higher levels of digital media use in multiple brain areas. These included the cuneus, lingual gyrus, supramarginal gyrus and postcentral gyrus.

The scans found accelerated maturation in certain basic areas, such as visual processing, but under-development in other higher-order areas that support more complex skills. Specifically, lower CT and SD have been linked to language development, reading skills and social skills such as complex memory encoding, empathy, and understanding facial and emotional expressions.

Findings were even stronger when looking specifically at brain areas where differences were linked to media use in a large, prior study involving adolescents ("ABCD" cohort study), published in 2019.

"At a minimum, findings in the current study involving visual areas are consistent with those in the ABCD study," Hutton says. "This suggests that relationships between higher media use and brain structure begin to manifest in early childhood and may become more extensive over time."

Findings expand upon earlier work

Hutton and colleagues have devoted years to studying potential impacts of screen time for children, including the first MRI-based studies in the formative preschool age range.

In 2018, the team reported in Brain Imaging and Behavior that functional connectivity between brain networks supporting language, imagery and other functions were strongest and most balanced during an illustrated storybook format compared to animated versions of similar stories. A follow-up study in the journal Brain Connectivity found optimal patterns of connectivity during illustrated compared to animated format involving brain networks supporting attention.

In January 2020, in JAMA Pediatrics, the team reported associations between higher screen usage and lower brain white-matter integrity and early literacy skills in preschool-age children.

In December 2021, in Pediatrics, experts at Cincinnati Children's further reported that shared reading time during early childhood was linked to lower social-emotional concerns later in life.

Hutton notes that the new research in young children dovetails with a recent finding from the ongoing Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study that reports associations between higher digital media use and lower CT and SD in areas involved with visual processing, executive functions, memory and attention, and with higher levels of behavior problems reported by parents.

What does this mean for families?

"These findings of differences in brain structure related to higher digital media use are especially important because the brain is growing so rapidly before age 5 and is exquisitely sensitive to experiences," Hutton says. "While not definitive and there is much work yet to be done, it is prudent for parents to be cautious regarding screen time at young ages, and to strive to keep use a minimum while encouraging 'analog' activities such as reading, talking and creative play."

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends limiting digital media use to no more than 1 hour a day for ages 2 to 5 and has urged parents to focus limited screen time usage to educational programs and to use together as much as possible.

The long-term effects of exposure to excessive screen time during early childhood have not yet been thoroughly studied because much of the technology involved is new, Hutton says, . Some disruptions to healthy development might be corrected over time because the brain can re-wire itself to adapt to harm or under-stimulation, though this becomes harder with age.

"The consistency of these brain findings involving young children and those involving teens suggests that there may be a cumulative impact of digital media use, which tends to increase with age," Hutton says. "Thus, limiting screen time and encouraging healthy alternatives as early as possible is a sound strategy to help children grow up healthy, well-adjusted and successful in school and life.

Hutton and colleagues plan to continue tracking the impacts of screen time as children grow, and to study the effectiveness of efforts to reduce potentially negative impacts of excessive use.

These Reading Programs Support Kindergarten Readiness

Learn more about the Reading and Literacy Discovery Center at Cincinnati Children’s

![]() View original content to download multimedia:https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/screen-usage-linked-to-differences-in-brain-structure-in-young-children-301674781.html

View original content to download multimedia:https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/screen-usage-linked-to-differences-in-brain-structure-in-young-children-301674781.html

SOURCE Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center